承接Python设计模式(3):结构型

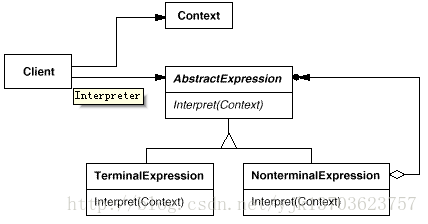

13. Interpreter(解释器)

意图:给定一个语言,定义它的文法的一种表示,并定义一个解释器,这个解释器使用该表示来解释语言中的句子。

适用性:

- 当有一个语言需要解释执行, 并且你可将该语言中的句子表示为一个抽象语法树时,可使用解释器模式。而当存在以下情况时该模式效果最好:

- 该文法简单对于复杂的文法, 文法的类层次变得庞大而无法管理。此时语法分析程序生成器这样的工具是更好的选择。它们无需构建抽象语法树即可解释表达式, 这样可以节省空间而且还可能节省时间。

- 效率不是一个关键问题最高效的解释器通常不是通过直接解释语法分析树实现的, 而是首先将它们转换成另一种形式。例如,正则表达式通常被转换成状态机。但即使在这种情况下, 转换器仍可用解释器模式实现, 该模式仍是有用的。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

‘‘‘

Interpreter

‘‘‘

class Context:

def __init__(self):

self.input=""

self.output=""

class AbstractExpression:

def Interpret(self,context):

pass

class Expression(AbstractExpression):

def Interpret(self,context):

print "terminal interpret"

class NonterminalExpression(AbstractExpression):

def Interpret(self,context):

print "Nonterminal interpret"

if __name__ == "__main__":

context= ""

c = []

c = c + [Expression()]

c = c + [NonterminalExpression()]

c = c + [Expression()]

c = c + [Expression()]

for a in c:

a.Interpret(context)- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

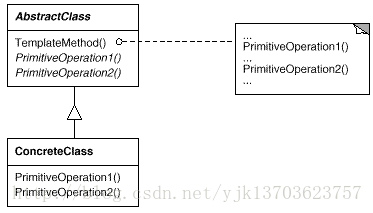

14. Template Method(模板方法)

意图:定义一个操作中的算法的骨架,而将一些步骤延迟到子类中。TemplateMethod 使得子类可以不改变一个算法的结构即可重定义该算法的某些特定步骤。

适用性:

- 一次性实现一个算法的不变的部分,并将可变的行为留给子类来实现。

- 各子类中公共的行为应被提取出来并集中到一个公共父类中以避免代码重复。这是Opdyke 和Johnson所描述过的“重分解以一般化”的一个很好的例子[ OJ93 ]。首先识别现有代码中的不同之处,并且将不同之处分离为新的操作。最后,用一个调用这些新的操作的模板方法来替换这些不同的代码。

- 控制子类扩展。模板方法只在特定点调用“hook ”操作(参见效果一节),这样就只允许在这些点进行扩展。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

‘‘‘

Template Method

‘‘‘

ingredients = "spam eggs apple"

line = ‘-‘ * 10

# Skeletons

def iter_elements(getter, action):

"""Template skeleton that iterates items"""

for element in getter():

action(element)

print(line)

def rev_elements(getter, action):

"""Template skeleton that iterates items in reverse order"""

for element in getter()[::-1]:

action(element)

print(line)

# Getters

def get_list():

return ingredients.split()

def get_lists():

return [list(x) for x in ingredients.split()]

# Actions

def print_item(item):

print(item)

def reverse_item(item):

print(item[::-1])

# Makes templates

def make_template(skeleton, getter, action):

"""Instantiate a template method with getter and action"""

def template():

skeleton(getter, action)

return template

# Create our template functions

templates = [make_template(s, g, a)

for g in (get_list, get_lists)

for a in (print_item, reverse_item)

for s in (iter_elements, rev_elements)]

# Execute them

for template in templates:

template()- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

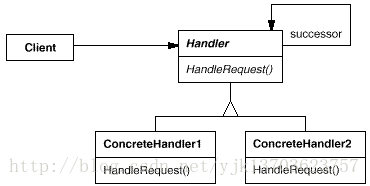

15. Chain of Responsibility(责任链)

意图:使多个对象都有机会处理请求,从而避免请求的发送者和接收者之间的耦合关系。将这些对象连成一条链,并沿着这条链传递该请求,直到有一个对象处理它为止。

适用性:

- 有多个的对象可以处理一个请求,哪个对象处理该请求运行时刻自动确定。

- 你想在不明确指定接收者的情况下,向多个对象中的一个提交一个请求。

- 可处理一个请求的对象集合应被动态指定。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

"""

Chain

"""

class Handler:

def successor(self, successor):

self.successor = successor

class ConcreteHandler1(Handler):

def handle(self, request):

if request > 0 and request <= 10:

print("in handler1")

else:

self.successor.handle(request)

class ConcreteHandler2(Handler):

def handle(self, request):

if request > 10 and request <= 20:

print("in handler2")

else:

self.successor.handle(request)

class ConcreteHandler3(Handler):

def handle(self, request):

if request > 20 and request <= 30:

print("in handler3")

else:

print(‘end of chain, no handler for {}‘.format(request))

class Client:

def __init__(self):

h1 = ConcreteHandler1()

h2 = ConcreteHandler2()

h3 = ConcreteHandler3()

h1.successor(h2)

h2.successor(h3)

requests = [2, 5, 14, 22, 18, 3, 35, 27, 20]

for request in requests:

h1.handle(request)

if __name__ == "__main__":

client = Client()- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

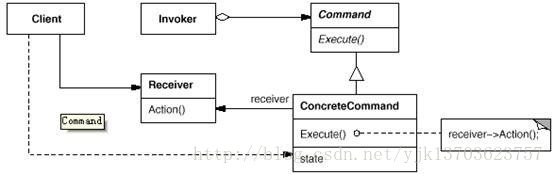

16. Command(命令)

意图:将一个请求封装为一个对象,从而使你可用不同的请求对客户进行参数化;对请求排队或记录请求日志,以及支持可撤消的操作。

适用性:

- 抽象出待执行的动作以参数化某对象,你可用过程语言中的回调(call back)函数表达这种参数化机制。所谓回调函数是指函数先在某处注册,而它将在稍后某个需要的时候被调用。Command 模式是回调机制的一个面向对象的替代品。

- 在不同的时刻指定、排列和执行请求。一个Command对象可以有一个与初始请求无关的生存期。如果一个请求的接收者可用一种与地址空间无关的方式表达,那么就可将负责该请求的命令对象传送给另一个不同的进程并在那儿实现该请求。

- 支持取消操作。Command的Excute 操作可在实施操作前将状态存储起来,在取消操作时这个状态用来消除该操作的影响。Command 接口必须添加一个Unexecute操作,该操作取消上一次Execute调用的效果。执行的命令被存储在一个历史列表中。可通过向后和向前遍历这一列表并分别调用Unexecute和Execute来实现重数不限的“取消”和“重做”。

- 支持修改日志,这样当系统崩溃时,这些修改可以被重做一遍。在Command接口中添加装载操作和存储操作,可以用来保持变动的一个一致的修改日志。从崩溃中恢复的过程包括从磁盘中重新读入记录下来的命令并用Execute操作重新执行它们。

- 用构建在原语操作上的高层操作构造一个系统。这样一种结构在支持事务( transaction)的信息系统中很常见。一个事务封装了对数据的一组变动。Command模式提供了对事务进行建模的方法。Command有一个公共的接口,使得你可以用同一种方式调用所有的事务。同时使用该模式也易于添加新事务以扩展系统。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

"""

Command

"""

import os

class MoveFileCommand(object):

def __init__(self, src, dest):

self.src = src

self.dest = dest

def execute(self):

self()

def __call__(self):

print(‘renaming {} to {}‘.format(self.src, self.dest))

os.rename(self.src, self.dest)

def undo(self):

print(‘renaming {} to {}‘.format(self.dest, self.src))

os.rename(self.dest, self.src)

if __name__ == "__main__":

command_stack = []

# commands are just pushed into the command stack

command_stack.append(MoveFileCommand(‘foo.txt‘, ‘bar.txt‘))

command_stack.append(MoveFileCommand(‘bar.txt‘, ‘baz.txt‘))

# they can be executed later on

for cmd in command_stack:

cmd.execute()

# and can also be undone at will

for cmd in reversed(command_stack):

cmd.undo()- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

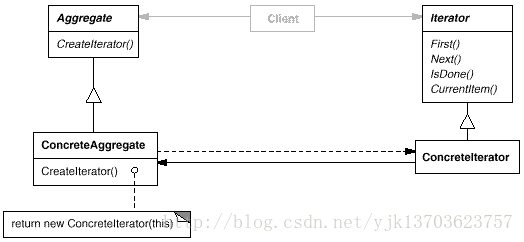

17. Iterator(迭代器)

意图:提供一种方法顺序访问一个聚合对象中各个元素, 而又不需暴露该对象的内部表示。

适用性:

- 访问一个聚合对象的内容而无需暴露它的内部表示。

- 支持对聚合对象的多种遍历。

- 为遍历不同的聚合结构提供一个统一的接口(即, 支持多态迭代)。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

‘‘‘

Interator

‘‘‘

def count_to(count):

"""Counts by word numbers, up to a maximum of five"""

numbers = ["one", "two", "three", "four", "five"]

# enumerate() returns a tuple containing a count (from start which

# defaults to 0) and the values obtained from iterating over sequence

for pos, number in zip(range(count), numbers):

yield number

# Test the generator

count_to_two = lambda: count_to(2)

count_to_five = lambda: count_to(5)

print(‘Counting to two...‘)

for number in count_to_two():

print number

print " "

print(‘Counting to five...‘)

for number in count_to_five():

print number

print " "- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

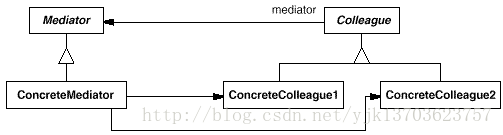

18. Mediator(中介者)

意图:用一个中介对象来封装一系列的对象交互。中介者使各对象不需要显式地相互引用,从而使其耦合松散,而且可以独立地改变它们之间的交互。

适用性:

- 一组对象以定义良好但是复杂的方式进行通信。产生的相互依赖关系结构混乱且难以理解。

- 一个对象引用其他很多对象并且直接与这些对象通信,导致难以复用该对象。

- 想定制一个分布在多个类中的行为,而又不想生成太多的子类。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

‘‘‘

Mediator

‘‘‘

"""http://dpip.testingperspective.com/?p=28"""

import time

class TC:

def __init__(self):

self._tm = tm

self._bProblem = 0

def setup(self):

print("Setting up the Test")

time.sleep(1)

self._tm.prepareReporting()

def execute(self):

if not self._bProblem:

print("Executing the test")

time.sleep(1)

else:

print("Problem in setup. Test not executed.")

def tearDown(self):

if not self._bProblem:

print("Tearing down")

time.sleep(1)

self._tm.publishReport()

else:

print("Test not executed. No tear down required.")

def setTM(self, TM):

self._tm = tm

def setProblem(self, value):

self._bProblem = value

class Reporter:

def __init__(self):

self._tm = None

def prepare(self):

print("Reporter Class is preparing to report the results")

time.sleep(1)

def report(self):

print("Reporting the results of Test")

time.sleep(1)

def setTM(self, TM):

self._tm = tm

class DB:

def __init__(self):

self._tm = None

def insert(self):

print("Inserting the execution begin status in the Database")

time.sleep(1)

#Following code is to simulate a communication from DB to TC

import random

if random.randrange(1, 4) == 3:

return -1

def update(self):

print("Updating the test results in Database")

time.sleep(1)

def setTM(self, TM):

self._tm = tm

class TestManager:

def __init__(self):

self._reporter = None

self._db = None

self._tc = None

def prepareReporting(self):

rvalue = self._db.insert()

if rvalue == -1:

self._tc.setProblem(1)

self._reporter.prepare()

def setReporter(self, reporter):

self._reporter = reporter

def setDB(self, db):

self._db = db

def publishReport(self):

self._db.update()

rvalue = self._reporter.report()

def setTC(self, tc):

self._tc = tc

if __name__ == ‘__main__‘:

reporter = Reporter()

db = DB()

tm = TestManager()

tm.setReporter(reporter)

tm.setDB(db)

reporter.setTM(tm)

db.setTM(tm)

# For simplification we are looping on the same test.

# Practically, it could be about various unique test classes and their

# objects

while (True):

tc = TC()

tc.setTM(tm)

tm.setTC(tc)

tc.setup()

tc.execute()

tc.tearDown()- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73

- 74

- 75

- 76

- 77

- 78

- 79

- 80

- 81

- 82

- 83

- 84

- 85

- 86

- 87

- 88

- 89

- 90

- 91

- 92

- 93

- 94

- 95

- 96

- 97

- 98

- 99

- 100

- 101

- 102

- 103

- 104

- 105

- 106

- 107

- 108

- 109

- 110

- 111

- 112

- 113

- 114

- 115

- 116

- 117

- 118

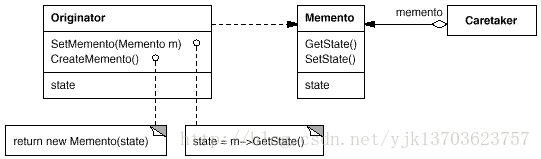

19. Memento(备忘录)

意图:在不破坏封装性的前提下,捕获一个对象的内部状态,并在该对象之外保存这个状态。这样以后就可将该对象恢复到原先保存的状态。

适用性:

- 必须保存一个对象在某一个时刻的(部分)状态, 这样以后需要时它才能恢复到先前的状态。

- 如果一个用接口来让其它对象直接得到这些状态,将会暴露对象的实现细节并破坏对象的封装性。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

‘‘‘

Memento

‘‘‘

import copy

def Memento(obj, deep=False):

state = (copy.copy, copy.deepcopy)[bool(deep)](obj.__dict__)

def Restore():

obj.__dict__.clear()

obj.__dict__.update(state)

return Restore

class Transaction:

"""A transaction guard. This is really just

syntactic suggar arount a memento closure.

"""

deep = False

def __init__(self, *targets):

self.targets = targets

self.Commit()

def Commit(self):

self.states = [Memento(target, self.deep) for target in self.targets]

def Rollback(self):

for st in self.states:

st()

class transactional(object):

"""Adds transactional semantics to methods. Methods decorated with

@transactional will rollback to entry state upon exceptions.

"""

def __init__(self, method):

self.method = method

def __get__(self, obj, T):

def transaction(*args, **kwargs):

state = Memento(obj)

try:

return self.method(obj, *args, **kwargs)

except:

state()

raise

return transaction

class NumObj(object):

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

def __repr__(self):

return ‘<%s: %r>‘ % (self.__class__.__name__, self.value)

def Increment(self):

self.value += 1

@transactional

def DoStuff(self):

self.value = ‘1111‘ # <- invalid value

self.Increment() # <- will fail and rollback

if __name__ == ‘__main__‘:

n = NumObj(-1)

print(n)

t = Transaction(n)

try:

for i in range(3):

n.Increment()

print(n)

t.Commit()

print(‘-- commited‘)

for i in range(3):

n.Increment()

print(n)

n.value += ‘x‘ # will fail

print(n)

except:

t.Rollback()

print(‘-- rolled back‘)

print(n)

print(‘-- now doing stuff ...‘)

try:

n.DoStuff()

except:

print(‘-> doing stuff failed!‘)

import traceback

traceback.print_exc(0)

pass

print(n)- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73

- 74

- 75

- 76

- 77

- 78

- 79

- 80

- 81

- 82

- 83

- 84

- 85

- 86

- 87

- 88

- 89

- 90

- 91

- 92

- 93

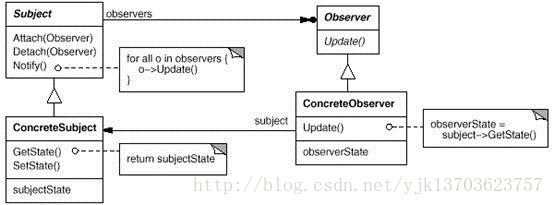

20. Observer(观察者)

意图:定义对象间的一种一对多的依赖关系,当一个对象的状态发生改变时, 所有依赖于它的对象都得到通知并被自动更新。

适用性:

- 当一个抽象模型有两个方面, 其中一个方面依赖于另一方面。将这二者封装在独立的对象中以使它们可以各自独立地改变和复用。

- 当对一个对象的改变需要同时改变其它对象, 而不知道具体有多少对象有待改变。

- 当一个对象必须通知其它对象,而它又不能假定其它对象是谁。换言之, 你不希望这些对象是紧密耦合的。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

‘‘‘

Observer

‘‘‘

class Subject(object):

def __init__(self):

self._observers = []

def attach(self, observer):

if not observer in self._observers:

self._observers.append(observer)

def detach(self, observer):

try:

self._observers.remove(observer)

except ValueError:

pass

def notify(self, modifier=None):

for observer in self._observers:

if modifier != observer:

observer.update(self)

# Example usage

class Data(Subject):

def __init__(self, name=‘‘):

Subject.__init__(self)

self.name = name

self._data = 0

@property

def data(self):

return self._data

@data.setter

def data(self, value):

self._data = value

self.notify()

class HexViewer:

def update(self, subject):

print(‘HexViewer: Subject %s has data 0x%x‘ %

(subject.name, subject.data))

class DecimalViewer:

def update(self, subject):

print(‘DecimalViewer: Subject %s has data %d‘ %

(subject.name, subject.data))

# Example usage...

def main():

data1 = Data(‘Data 1‘)

data2 = Data(‘Data 2‘)

view1 = DecimalViewer()

view2 = HexViewer()

data1.attach(view1)

data1.attach(view2)

data2.attach(view2)

data2.attach(view1)

print("Setting Data 1 = 10")

data1.data = 10

print("Setting Data 2 = 15")

data2.data = 15

print("Setting Data 1 = 3")

data1.data = 3

print("Setting Data 2 = 5")

data2.data = 5

print("Detach HexViewer from data1 and data2.")

data1.detach(view2)

data2.detach(view2)

print("Setting Data 1 = 10")

data1.data = 10

print("Setting Data 2 = 15")

data2.data = 15

if __name__ == ‘__main__‘:

main()- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73

- 74

- 75

- 76

- 77

- 78

- 79

- 80

- 81

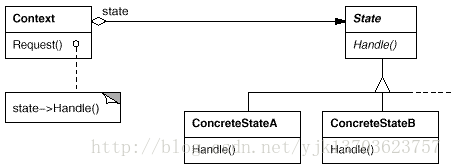

21. State(状态)

意图:允许一个对象在其内部状态改变时改变它的行为。对象看起来似乎修改了它的类。

适用性:

- 一个对象的行为取决于它的状态, 并且它必须在运行时刻根据状态改变它的行为。

- 一个操作中含有庞大的多分支的条件语句,且这些分支依赖于该对象的状态。这个状态通常用一个或多个枚举常量表示。通常, 有多个操作包含这一相同的条件结构。State模式将每一个条件分支放入一个独立的类中。这使得你可以根据对象自身的情况将对象的状态作为一个对象,这一对象可以不依赖于其他对象而独立变化。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

‘‘‘

State

‘‘‘

class State(object):

"""Base state. This is to share functionality"""

def scan(self):

"""Scan the dial to the next station"""

self.pos += 1

if self.pos == len(self.stations):

self.pos = 0

print("Scanning... Station is", self.stations[self.pos], self.name)

class AmState(State):

def __init__(self, radio):

self.radio = radio

self.stations = ["1250", "1380", "1510"]

self.pos = 0

self.name = "AM"

def toggle_amfm(self):

print("Switching to FM")

self.radio.state = self.radio.fmstate

class FmState(State):

def __init__(self, radio):

self.radio = radio

self.stations = ["81.3", "89.1", "103.9"]

self.pos = 0

self.name = "FM"

def toggle_amfm(self):

print("Switching to AM")

self.radio.state = self.radio.amstate

class Radio(object):

"""A radio. It has a scan button, and an AM/FM toggle switch."""

def __init__(self):

"""We have an AM state and an FM state"""

self.amstate = AmState(self)

self.fmstate = FmState(self)

self.state = self.amstate

def toggle_amfm(self):

self.state.toggle_amfm()

def scan(self):

self.state.scan()

# Test our radio out

if __name__ == ‘__main__‘:

radio = Radio()

actions = [radio.scan] * 2 + [radio.toggle_amfm] + [radio.scan] * 2

actions = actions * 2

for action in actions:

action()- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

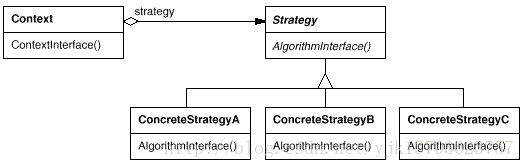

22. Strategy(策略)

意图:定义一系列的算法,把它们一个个封装起来, 并且使它们可相互替换。本模式使得算法可独立于使用它的客户而变化。

适用性:

- 许多相关的类仅仅是行为有异。“策略”提供了一种用多个行为中的一个行为来配置一个类的方法。

- 需要使用一个算法的不同变体。例如,你可能会定义一些反映不同的空间/时间权衡的算法。当这些变体实现为一个算法的类层次时[H087] ,可以使用策略模式。

- 算法使用客户不应该知道的数据。可使用策略模式以避免暴露复杂的、与算法相关的数据结构。

- 一个类定义了多种行为, 并且这些行为在这个类的操作中以多个条件语句的形式出现。将相关的条件分支移入它们各自的Strategy类中以代替这些条件语句。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

"""

Strategy

In most of other languages Strategy pattern is implemented via creating some base strategy interface/abstract class and

subclassing it with a number of concrete strategies (as we can see at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strategy_pattern),

however Python supports higher-order functions and allows us to have only one class and inject functions into it‘s

instances, as shown in this example.

"""

import types

class StrategyExample:

def __init__(self, func=None):

self.name = ‘Strategy Example 0‘

if func is not None:

self.execute = types.MethodType(func, self)

def execute(self):

print(self.name)

def execute_replacement1(self):

print(self.name + ‘ from execute 1‘)

def execute_replacement2(self):

print(self.name + ‘ from execute 2‘)

if __name__ == ‘__main__‘:

strat0 = StrategyExample()

strat1 = StrategyExample(execute_replacement1)

strat1.name = ‘Strategy Example 1‘

strat2 = StrategyExample(execute_replacement2)

strat2.name = ‘Strategy Example 2‘

strat0.execute()

strat1.execute()

strat2.execute()- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

23. Visitor(访问者)

意图:定义一个操作中的算法的骨架,而将一些步骤延迟到子类中。TemplateMethod 使得子类可以不改变一个算法的结构即可重定义该算法的某些特定步骤。

适用性:

- 一次性实现一个算法的不变的部分,并将可变的行为留给子类来实现。

- 各子类中公共的行为应被提取出来并集中到一个公共父类中以避免代码重复。这是Opdyke和Johnson所描述过的“重分解以一般化”的一个很好的例子[OJ93]。首先识别现有代码中的不同之处,并且将不同之处分离为新的操作。最后,用一个调用这些新的操作的模板方法来替换这些不同的代码。

- 控制子类扩展。模板方法只在特定点调用“hook ”操作(参见效果一节),这样就只允许在这些点进行扩展。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

‘‘‘

Visitor

‘‘‘

class Node(object):

pass

class A(Node):

pass

class B(Node):

pass

class C(A, B):

pass

class Visitor(object):

def visit(self, node, *args, **kwargs):

meth = None

for cls in node.__class__.__mro__:

meth_name = ‘visit_‘+cls.__name__

meth = getattr(self, meth_name, None)

if meth:

break

if not meth:

meth = self.generic_visit

return meth(node, *args, **kwargs)

def generic_visit(self, node, *args, **kwargs):

print(‘generic_visit ‘+node.__class__.__name__)

def visit_B(self, node, *args, **kwargs):

print(‘visit_B ‘+node.__class__.__name__)

a = A()

b = B()

c = C()

visitor = Visitor()

visitor.visit(a)

visitor.visit(b)

visitor.visit(c)- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

参考文章

https://www.cnblogs.com/Liqiongyu/p/5916710.html

承接Python设计模式(3):结构型

13. Interpreter(解释器)

意图:给定一个语言,定义它的文法的一种表示,并定义一个解释器,这个解释器使用该表示来解释语言中的句子。

适用性:

- 当有一个语言需要解释执行, 并且你可将该语言中的句子表示为一个抽象语法树时,可使用解释器模式。而当存在以下情况时该模式效果最好:

- 该文法简单对于复杂的文法, 文法的类层次变得庞大而无法管理。此时语法分析程序生成器这样的工具是更好的选择。它们无需构建抽象语法树即可解释表达式, 这样可以节省空间而且还可能节省时间。

- 效率不是一个关键问题最高效的解释器通常不是通过直接解释语法分析树实现的, 而是首先将它们转换成另一种形式。例如,正则表达式通常被转换成状态机。但即使在这种情况下, 转换器仍可用解释器模式实现, 该模式仍是有用的。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

‘‘‘

Interpreter

‘‘‘

class Context:

def __init__(self):

self.input=""

self.output=""

class AbstractExpression:

def Interpret(self,context):

pass

class Expression(AbstractExpression):

def Interpret(self,context):

print "terminal interpret"

class NonterminalExpression(AbstractExpression):

def Interpret(self,context):

print "Nonterminal interpret"

if __name__ == "__main__":

context= ""

c = []

c = c + [Expression()]

c = c + [NonterminalExpression()]

c = c + [Expression()]

c = c + [Expression()]

for a in c:

a.Interpret(context)- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

14. Template Method(模板方法)

意图:定义一个操作中的算法的骨架,而将一些步骤延迟到子类中。TemplateMethod 使得子类可以不改变一个算法的结构即可重定义该算法的某些特定步骤。

适用性:

- 一次性实现一个算法的不变的部分,并将可变的行为留给子类来实现。

- 各子类中公共的行为应被提取出来并集中到一个公共父类中以避免代码重复。这是Opdyke 和Johnson所描述过的“重分解以一般化”的一个很好的例子[ OJ93 ]。首先识别现有代码中的不同之处,并且将不同之处分离为新的操作。最后,用一个调用这些新的操作的模板方法来替换这些不同的代码。

- 控制子类扩展。模板方法只在特定点调用“hook ”操作(参见效果一节),这样就只允许在这些点进行扩展。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

‘‘‘

Template Method

‘‘‘

ingredients = "spam eggs apple"

line = ‘-‘ * 10

# Skeletons

def iter_elements(getter, action):

"""Template skeleton that iterates items"""

for element in getter():

action(element)

print(line)

def rev_elements(getter, action):

"""Template skeleton that iterates items in reverse order"""

for element in getter()[::-1]:

action(element)

print(line)

# Getters

def get_list():

return ingredients.split()

def get_lists():

return [list(x) for x in ingredients.split()]

# Actions

def print_item(item):

print(item)

def reverse_item(item):

print(item[::-1])

# Makes templates

def make_template(skeleton, getter, action):

"""Instantiate a template method with getter and action"""

def template():

skeleton(getter, action)

return template

# Create our template functions

templates = [make_template(s, g, a)

for g in (get_list, get_lists)

for a in (print_item, reverse_item)

for s in (iter_elements, rev_elements)]

# Execute them

for template in templates:

template()- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

15. Chain of Responsibility(责任链)

意图:使多个对象都有机会处理请求,从而避免请求的发送者和接收者之间的耦合关系。将这些对象连成一条链,并沿着这条链传递该请求,直到有一个对象处理它为止。

适用性:

- 有多个的对象可以处理一个请求,哪个对象处理该请求运行时刻自动确定。

- 你想在不明确指定接收者的情况下,向多个对象中的一个提交一个请求。

- 可处理一个请求的对象集合应被动态指定。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

"""

Chain

"""

class Handler:

def successor(self, successor):

self.successor = successor

class ConcreteHandler1(Handler):

def handle(self, request):

if request > 0 and request <= 10:

print("in handler1")

else:

self.successor.handle(request)

class ConcreteHandler2(Handler):

def handle(self, request):

if request > 10 and request <= 20:

print("in handler2")

else:

self.successor.handle(request)

class ConcreteHandler3(Handler):

def handle(self, request):

if request > 20 and request <= 30:

print("in handler3")

else:

print(‘end of chain, no handler for {}‘.format(request))

class Client:

def __init__(self):

h1 = ConcreteHandler1()

h2 = ConcreteHandler2()

h3 = ConcreteHandler3()

h1.successor(h2)

h2.successor(h3)

requests = [2, 5, 14, 22, 18, 3, 35, 27, 20]

for request in requests:

h1.handle(request)

if __name__ == "__main__":

client = Client()- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

16. Command(命令)

意图:将一个请求封装为一个对象,从而使你可用不同的请求对客户进行参数化;对请求排队或记录请求日志,以及支持可撤消的操作。

适用性:

- 抽象出待执行的动作以参数化某对象,你可用过程语言中的回调(call back)函数表达这种参数化机制。所谓回调函数是指函数先在某处注册,而它将在稍后某个需要的时候被调用。Command 模式是回调机制的一个面向对象的替代品。

- 在不同的时刻指定、排列和执行请求。一个Command对象可以有一个与初始请求无关的生存期。如果一个请求的接收者可用一种与地址空间无关的方式表达,那么就可将负责该请求的命令对象传送给另一个不同的进程并在那儿实现该请求。

- 支持取消操作。Command的Excute 操作可在实施操作前将状态存储起来,在取消操作时这个状态用来消除该操作的影响。Command 接口必须添加一个Unexecute操作,该操作取消上一次Execute调用的效果。执行的命令被存储在一个历史列表中。可通过向后和向前遍历这一列表并分别调用Unexecute和Execute来实现重数不限的“取消”和“重做”。

- 支持修改日志,这样当系统崩溃时,这些修改可以被重做一遍。在Command接口中添加装载操作和存储操作,可以用来保持变动的一个一致的修改日志。从崩溃中恢复的过程包括从磁盘中重新读入记录下来的命令并用Execute操作重新执行它们。

- 用构建在原语操作上的高层操作构造一个系统。这样一种结构在支持事务( transaction)的信息系统中很常见。一个事务封装了对数据的一组变动。Command模式提供了对事务进行建模的方法。Command有一个公共的接口,使得你可以用同一种方式调用所有的事务。同时使用该模式也易于添加新事务以扩展系统。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

"""

Command

"""

import os

class MoveFileCommand(object):

def __init__(self, src, dest):

self.src = src

self.dest = dest

def execute(self):

self()

def __call__(self):

print(‘renaming {} to {}‘.format(self.src, self.dest))

os.rename(self.src, self.dest)

def undo(self):

print(‘renaming {} to {}‘.format(self.dest, self.src))

os.rename(self.dest, self.src)

if __name__ == "__main__":

command_stack = []

# commands are just pushed into the command stack

command_stack.append(MoveFileCommand(‘foo.txt‘, ‘bar.txt‘))

command_stack.append(MoveFileCommand(‘bar.txt‘, ‘baz.txt‘))

# they can be executed later on

for cmd in command_stack:

cmd.execute()

# and can also be undone at will

for cmd in reversed(command_stack):

cmd.undo()- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

17. Iterator(迭代器)

意图:提供一种方法顺序访问一个聚合对象中各个元素, 而又不需暴露该对象的内部表示。

适用性:

- 访问一个聚合对象的内容而无需暴露它的内部表示。

- 支持对聚合对象的多种遍历。

- 为遍历不同的聚合结构提供一个统一的接口(即, 支持多态迭代)。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

‘‘‘

Interator

‘‘‘

def count_to(count):

"""Counts by word numbers, up to a maximum of five"""

numbers = ["one", "two", "three", "four", "five"]

# enumerate() returns a tuple containing a count (from start which

# defaults to 0) and the values obtained from iterating over sequence

for pos, number in zip(range(count), numbers):

yield number

# Test the generator

count_to_two = lambda: count_to(2)

count_to_five = lambda: count_to(5)

print(‘Counting to two...‘)

for number in count_to_two():

print number

print " "

print(‘Counting to five...‘)

for number in count_to_five():

print number

print " "- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

18. Mediator(中介者)

意图:用一个中介对象来封装一系列的对象交互。中介者使各对象不需要显式地相互引用,从而使其耦合松散,而且可以独立地改变它们之间的交互。

适用性:

- 一组对象以定义良好但是复杂的方式进行通信。产生的相互依赖关系结构混乱且难以理解。

- 一个对象引用其他很多对象并且直接与这些对象通信,导致难以复用该对象。

- 想定制一个分布在多个类中的行为,而又不想生成太多的子类。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

‘‘‘

Mediator

‘‘‘

"""http://dpip.testingperspective.com/?p=28"""

import time

class TC:

def __init__(self):

self._tm = tm

self._bProblem = 0

def setup(self):

print("Setting up the Test")

time.sleep(1)

self._tm.prepareReporting()

def execute(self):

if not self._bProblem:

print("Executing the test")

time.sleep(1)

else:

print("Problem in setup. Test not executed.")

def tearDown(self):

if not self._bProblem:

print("Tearing down")

time.sleep(1)

self._tm.publishReport()

else:

print("Test not executed. No tear down required.")

def setTM(self, TM):

self._tm = tm

def setProblem(self, value):

self._bProblem = value

class Reporter:

def __init__(self):

self._tm = None

def prepare(self):

print("Reporter Class is preparing to report the results")

time.sleep(1)

def report(self):

print("Reporting the results of Test")

time.sleep(1)

def setTM(self, TM):

self._tm = tm

class DB:

def __init__(self):

self._tm = None

def insert(self):

print("Inserting the execution begin status in the Database")

time.sleep(1)

#Following code is to simulate a communication from DB to TC

import random

if random.randrange(1, 4) == 3:

return -1

def update(self):

print("Updating the test results in Database")

time.sleep(1)

def setTM(self, TM):

self._tm = tm

class TestManager:

def __init__(self):

self._reporter = None

self._db = None

self._tc = None

def prepareReporting(self):

rvalue = self._db.insert()

if rvalue == -1:

self._tc.setProblem(1)

self._reporter.prepare()

def setReporter(self, reporter):

self._reporter = reporter

def setDB(self, db):

self._db = db

def publishReport(self):

self._db.update()

rvalue = self._reporter.report()

def setTC(self, tc):

self._tc = tc

if __name__ == ‘__main__‘:

reporter = Reporter()

db = DB()

tm = TestManager()

tm.setReporter(reporter)

tm.setDB(db)

reporter.setTM(tm)

db.setTM(tm)

# For simplification we are looping on the same test.

# Practically, it could be about various unique test classes and their

# objects

while (True):

tc = TC()

tc.setTM(tm)

tm.setTC(tc)

tc.setup()

tc.execute()

tc.tearDown()- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73

- 74

- 75

- 76

- 77

- 78

- 79

- 80

- 81

- 82

- 83

- 84

- 85

- 86

- 87

- 88

- 89

- 90

- 91

- 92

- 93

- 94

- 95

- 96

- 97

- 98

- 99

- 100

- 101

- 102

- 103

- 104

- 105

- 106

- 107

- 108

- 109

- 110

- 111

- 112

- 113

- 114

- 115

- 116

- 117

- 118

19. Memento(备忘录)

意图:在不破坏封装性的前提下,捕获一个对象的内部状态,并在该对象之外保存这个状态。这样以后就可将该对象恢复到原先保存的状态。

适用性:

- 必须保存一个对象在某一个时刻的(部分)状态, 这样以后需要时它才能恢复到先前的状态。

- 如果一个用接口来让其它对象直接得到这些状态,将会暴露对象的实现细节并破坏对象的封装性。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

‘‘‘

Memento

‘‘‘

import copy

def Memento(obj, deep=False):

state = (copy.copy, copy.deepcopy)[bool(deep)](obj.__dict__)

def Restore():

obj.__dict__.clear()

obj.__dict__.update(state)

return Restore

class Transaction:

"""A transaction guard. This is really just

syntactic suggar arount a memento closure.

"""

deep = False

def __init__(self, *targets):

self.targets = targets

self.Commit()

def Commit(self):

self.states = [Memento(target, self.deep) for target in self.targets]

def Rollback(self):

for st in self.states:

st()

class transactional(object):

"""Adds transactional semantics to methods. Methods decorated with

@transactional will rollback to entry state upon exceptions.

"""

def __init__(self, method):

self.method = method

def __get__(self, obj, T):

def transaction(*args, **kwargs):

state = Memento(obj)

try:

return self.method(obj, *args, **kwargs)

except:

state()

raise

return transaction

class NumObj(object):

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

def __repr__(self):

return ‘<%s: %r>‘ % (self.__class__.__name__, self.value)

def Increment(self):

self.value += 1

@transactional

def DoStuff(self):

self.value = ‘1111‘ # <- invalid value

self.Increment() # <- will fail and rollback

if __name__ == ‘__main__‘:

n = NumObj(-1)

print(n)

t = Transaction(n)

try:

for i in range(3):

n.Increment()

print(n)

t.Commit()

print(‘-- commited‘)

for i in range(3):

n.Increment()

print(n)

n.value += ‘x‘ # will fail

print(n)

except:

t.Rollback()

print(‘-- rolled back‘)

print(n)

print(‘-- now doing stuff ...‘)

try:

n.DoStuff()

except:

print(‘-> doing stuff failed!‘)

import traceback

traceback.print_exc(0)

pass

print(n)- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73

- 74

- 75

- 76

- 77

- 78

- 79

- 80

- 81

- 82

- 83

- 84

- 85

- 86

- 87

- 88

- 89

- 90

- 91

- 92

- 93

20. Observer(观察者)

意图:定义对象间的一种一对多的依赖关系,当一个对象的状态发生改变时, 所有依赖于它的对象都得到通知并被自动更新。

适用性:

- 当一个抽象模型有两个方面, 其中一个方面依赖于另一方面。将这二者封装在独立的对象中以使它们可以各自独立地改变和复用。

- 当对一个对象的改变需要同时改变其它对象, 而不知道具体有多少对象有待改变。

- 当一个对象必须通知其它对象,而它又不能假定其它对象是谁。换言之, 你不希望这些对象是紧密耦合的。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

‘‘‘

Observer

‘‘‘

class Subject(object):

def __init__(self):

self._observers = []

def attach(self, observer):

if not observer in self._observers:

self._observers.append(observer)

def detach(self, observer):

try:

self._observers.remove(observer)

except ValueError:

pass

def notify(self, modifier=None):

for observer in self._observers:

if modifier != observer:

observer.update(self)

# Example usage

class Data(Subject):

def __init__(self, name=‘‘):

Subject.__init__(self)

self.name = name

self._data = 0

@property

def data(self):

return self._data

@data.setter

def data(self, value):

self._data = value

self.notify()

class HexViewer:

def update(self, subject):

print(‘HexViewer: Subject %s has data 0x%x‘ %

(subject.name, subject.data))

class DecimalViewer:

def update(self, subject):

print(‘DecimalViewer: Subject %s has data %d‘ %

(subject.name, subject.data))

# Example usage...

def main():

data1 = Data(‘Data 1‘)

data2 = Data(‘Data 2‘)

view1 = DecimalViewer()

view2 = HexViewer()

data1.attach(view1)

data1.attach(view2)

data2.attach(view2)

data2.attach(view1)

print("Setting Data 1 = 10")

data1.data = 10

print("Setting Data 2 = 15")

data2.data = 15

print("Setting Data 1 = 3")

data1.data = 3

print("Setting Data 2 = 5")

data2.data = 5

print("Detach HexViewer from data1 and data2.")

data1.detach(view2)

data2.detach(view2)

print("Setting Data 1 = 10")

data1.data = 10

print("Setting Data 2 = 15")

data2.data = 15

if __name__ == ‘__main__‘:

main()- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73

- 74

- 75

- 76

- 77

- 78

- 79

- 80

- 81

21. State(状态)

意图:允许一个对象在其内部状态改变时改变它的行为。对象看起来似乎修改了它的类。

适用性:

- 一个对象的行为取决于它的状态, 并且它必须在运行时刻根据状态改变它的行为。

- 一个操作中含有庞大的多分支的条件语句,且这些分支依赖于该对象的状态。这个状态通常用一个或多个枚举常量表示。通常, 有多个操作包含这一相同的条件结构。State模式将每一个条件分支放入一个独立的类中。这使得你可以根据对象自身的情况将对象的状态作为一个对象,这一对象可以不依赖于其他对象而独立变化。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

‘‘‘

State

‘‘‘

class State(object):

"""Base state. This is to share functionality"""

def scan(self):

"""Scan the dial to the next station"""

self.pos += 1

if self.pos == len(self.stations):

self.pos = 0

print("Scanning... Station is", self.stations[self.pos], self.name)

class AmState(State):

def __init__(self, radio):

self.radio = radio

self.stations = ["1250", "1380", "1510"]

self.pos = 0

self.name = "AM"

def toggle_amfm(self):

print("Switching to FM")

self.radio.state = self.radio.fmstate

class FmState(State):

def __init__(self, radio):

self.radio = radio

self.stations = ["81.3", "89.1", "103.9"]

self.pos = 0

self.name = "FM"

def toggle_amfm(self):

print("Switching to AM")

self.radio.state = self.radio.amstate

class Radio(object):

"""A radio. It has a scan button, and an AM/FM toggle switch."""

def __init__(self):

"""We have an AM state and an FM state"""

self.amstate = AmState(self)

self.fmstate = FmState(self)

self.state = self.amstate

def toggle_amfm(self):

self.state.toggle_amfm()

def scan(self):

self.state.scan()

# Test our radio out

if __name__ == ‘__main__‘:

radio = Radio()

actions = [radio.scan] * 2 + [radio.toggle_amfm] + [radio.scan] * 2

actions = actions * 2

for action in actions:

action()- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

22. Strategy(策略)

意图:定义一系列的算法,把它们一个个封装起来, 并且使它们可相互替换。本模式使得算法可独立于使用它的客户而变化。

适用性:

- 许多相关的类仅仅是行为有异。“策略”提供了一种用多个行为中的一个行为来配置一个类的方法。

- 需要使用一个算法的不同变体。例如,你可能会定义一些反映不同的空间/时间权衡的算法。当这些变体实现为一个算法的类层次时[H087] ,可以使用策略模式。

- 算法使用客户不应该知道的数据。可使用策略模式以避免暴露复杂的、与算法相关的数据结构。

- 一个类定义了多种行为, 并且这些行为在这个类的操作中以多个条件语句的形式出现。将相关的条件分支移入它们各自的Strategy类中以代替这些条件语句。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

"""

Strategy

In most of other languages Strategy pattern is implemented via creating some base strategy interface/abstract class and

subclassing it with a number of concrete strategies (as we can see at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strategy_pattern),

however Python supports higher-order functions and allows us to have only one class and inject functions into it‘s

instances, as shown in this example.

"""

import types

class StrategyExample:

def __init__(self, func=None):

self.name = ‘Strategy Example 0‘

if func is not None:

self.execute = types.MethodType(func, self)

def execute(self):

print(self.name)

def execute_replacement1(self):

print(self.name + ‘ from execute 1‘)

def execute_replacement2(self):

print(self.name + ‘ from execute 2‘)

if __name__ == ‘__main__‘:

strat0 = StrategyExample()

strat1 = StrategyExample(execute_replacement1)

strat1.name = ‘Strategy Example 1‘

strat2 = StrategyExample(execute_replacement2)

strat2.name = ‘Strategy Example 2‘

strat0.execute()

strat1.execute()

strat2.execute()- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

23. Visitor(访问者)

意图:定义一个操作中的算法的骨架,而将一些步骤延迟到子类中。TemplateMethod 使得子类可以不改变一个算法的结构即可重定义该算法的某些特定步骤。

适用性:

- 一次性实现一个算法的不变的部分,并将可变的行为留给子类来实现。

- 各子类中公共的行为应被提取出来并集中到一个公共父类中以避免代码重复。这是Opdyke和Johnson所描述过的“重分解以一般化”的一个很好的例子[OJ93]。首先识别现有代码中的不同之处,并且将不同之处分离为新的操作。最后,用一个调用这些新的操作的模板方法来替换这些不同的代码。

- 控制子类扩展。模板方法只在特定点调用“hook ”操作(参见效果一节),这样就只允许在这些点进行扩展。

#!/usr/bin/python

#coding:utf8

‘‘‘

Visitor

‘‘‘

class Node(object):

pass

class A(Node):

pass

class B(Node):

pass

class C(A, B):

pass

class Visitor(object):

def visit(self, node, *args, **kwargs):

meth = None

for cls in node.__class__.__mro__:

meth_name = ‘visit_‘+cls.__name__

meth = getattr(self, meth_name, None)

if meth:

break

if not meth:

meth = self.generic_visit

return meth(node, *args, **kwargs)

def generic_visit(self, node, *args, **kwargs):

print(‘generic_visit ‘+node.__class__.__name__)

def visit_B(self, node, *args, **kwargs):

print(‘visit_B ‘+node.__class__.__name__)

a = A()

b = B()

c = C()

visitor = Visitor()

visitor.visit(a)

visitor.visit(b)

visitor.visit(c)- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

参考文章

https://www.cnblogs.com/Liqiongyu/p/5916710.html

原文地址:https://www.cnblogs.com/mac1993/p/9300924.html